The collapse of Evergrande, one of China’s largest property developers, has sent shockwaves through global financial markets. As the company grapples with a massive debt crisis, its impending default raises concerns about the broader implications for China’s economy and the global real estate sector.

China’s Minsky Moment has now materialized, a decade after the country embarked on policies cautioned against by Minsky, which were predicted to render its financial system vulnerable and its economy precarious. The future course for China remains uncertain, but Minsky’s framework for understanding financial instability offers valuable insights for assessing the risks.

History often foreshadows risks. A decade ago, the vulnerabilities in China’s economy and financial system were mere possibilities, not certainties. However, as I noted in my writings in 2015 and 2017, they were formidable probabilities.

Looking ahead, China faces substantial risks. These include the possibility of further escalating debt levels, investments in unproductive ventures, diminished competitiveness compared to certain Asian neighbors, sluggish economic growth, internal social unrest, and an increasingly assertive military stance.

A “Minsky moment” refers to a significant asset price bubble bursting following a period of excessive optimism, increased borrowing, a rapidly growing shadow banking sector, the development of innovative speculative finance instruments, and lax regulation.

While economist Hyman Minsky did not use the term himself, it was coined by Paul McCulley. The risks associated with China’s current situation align with Minsky’s framework, which categorizes post-Minsky moment events into four policy areas: fiscal, monetary, labor, and industrial policies.

Robert Aliber, a respected economist and co-author of the influential book “Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises,” has been closely observing China’s economic and financial situation. He warned about a significant real estate market bubble in China in 2015, and as of the end of 2022, he discussed the repercussions of the bubble’s burst, drawing parallels with Japan’s experience. Aliber bluntly suggests that China in the 2020s will resemble Japan in the 1990s, when Japan’s growth rate plummeted after the bursting of its real estate bubble in the 1980s.

Of particular importance is Aliber’s analysis of the relationship between Japan’s financial markets and its real economy during its Minsky moment. He identified the key challenge for Japan’s growth in the 1990s, which was the need to reduce debt and resolve the consequences of the collapses in its real estate and stock markets. It’s worth noting that many factors that had driven Japan’s high growth rate in the 1980s, such as a high savings rate, government support for industries, and industrial competitiveness, remained intact in the 1990s.

Hyman Minsky coined the term “Ponzi finance” to describe a situation where debt repayment depends on the appreciation of collateral’s value rather than income generated by the collateral itself. He cautioned that such practices fuel bubbles and make financial markets more fragile.

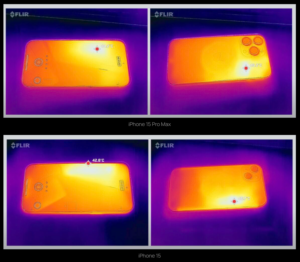

Robert Aliber discusses the case of China’s Evergrande, a property developer currently facing significant challenges. Evergrande and similar developers engaged in Ponzi finance by using down payments from new buyers to pay for the construction of properties promised to earlier buyers. China’s construction boom was driven by rural-to-urban migration, but when this slowed and demand for urban apartments decreased, a Minsky moment occurred.

The drop in apartment purchases led to declining prices, making it difficult for property developers like Evergrande to secure funding for their ongoing projects. Lenders became hesitant to finance projects with falling property values, contributing to Evergrande’s current crisis.

Minsky’s analysis of the aftermath of a burst bubble highlights several key government responses: increased public sector spending to stabilize the economy, keeping interest rates low to stimulate spending and job creation, bailing out too-big-to-fail financial institutions, and scrutinizing large corporations. China is currently experiencing these phenomena, as reported in a recent Wall Street Journal article. The Chinese government is involved in large infrastructure projects, reducing interest rates, and preparing to recapitalize failing financial firms through substantial debt issuance. Additionally, they have imposed constraints on prominent entrepreneurs like Jack Ma, aligning with China’s political traditions.

In contrast to the United States’ real estate bubble burst during the financial crisis, where household wealth declined by half the GDP, China faces a much more significant challenge, with a decline potentially ten times its GDP. This could lead to considerable frustration among Chinese households with high expectations for a better future. Despite these challenges, China’s current household income remains relatively low compared to “high-income” countries, making it unlikely for Chinese households to accept income declines willingly. As a result, China may face reduced competitiveness compared to its Asian neighbors like Vietnam and Bangladesh.

The structural weaknesses in China’s economic and financial system are profound and enduring, and the country’s leaders have ambitious goals and a strong desire to maintain their reputation. This combination may lead to risk-taking behaviors, including potential military actions, as China seeks to avoid falling short of its aspirations.

Hyman Minsky acknowledged that achieving economic gains in a capitalist system often involves taking risks, even if it means risking financial instability. He suggested that reducing the possibility of a financial disaster might dampen the creativity and dynamism of the capitalist system. This principle applies to all capitalist economies, including China.

In the past decade, what distinguished China from other nations was its leaders’ willingness to embrace substantial risks. When evaluating the current risks facing China, it’s essential to remember this characteristic and its implications for the country’s economic and financial stability.

(Source: Hersh Shefrin | Forbes)